Reading the “Internet+” Smart Energy Development Guidelines

On February 29th, 2016, the NDRC, NEA, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology released Guiding Opinions on “Internet+” Smart Energy Development.

This policy document focuses on the Energy Internet, a concept which has engulfed Chinese energy and grid circles for more than a year.

With the release of this document, we have an official take on the future of China’s grid.

The Opinions established a definition for this Energy Internet concept: “a new industry development model based on a deeply integrated network of energy production, transmission, storage, consumption and markets. It is characterized by device intelligence, energy diversity, information symmetry, distributed generation and demand, a flat structure, and open exchange.”

Until now, energy storage in China has been perceived as a set of technologies or devices used in certain links in the grid. But the Opinions take a different approach, describing energy storage as a standalone link in the energy chain, alongside production, transmission, and consumption. This is the first time that national government bodies have recognized energy storage as a separate and critical part of the future energy system.

The Energy Internet covers power, heat, oil and gas, and transportation. By highlighting energy storage as an independent link in the energy chain, policymakers are laying a foundation for the beneficial use of energy storage across the board.

The Opinions take a broad look at energy storage, calling for the development of “high-capacity, low-cost, high-efficiency and long-lived energy storage products and systems in electricity, thermal, and clean fuel storage.” This inclusive approach places energy storage at the center of the interconnections between power, heat, transportation and gas networks.

Bulk Energy Storage and Renewables Integration

The Opinions argue “suitably-sized energy storage facilities should be located in energy production centers to optimize grid and energy system operation."

At present, energy storage facilities used for renewables integration are generation-side resources, co-located with particular power stations. The Opinions call on years of operational experience and institutional input to suggest that energy storage functions better as a shared resource located in areas with high energy production. This maximizes the value of expensive storage installations by serving multiple stations at once.

Better sited energy storage would also gain value by giving grid operators the ability to tap into other operational benefits of the technology.

Some experts estimate that energy storage installations equaling 5-10% of the generation capacity in a renewable energy producing region would be sufficient to address intermittency issues. With China’s 12th Five-Year Plan calling for 200 gigawatts of wind by 2020, the grid would benefit from an additional 10-20 gigawatts of energy storage – an enormous opportunity.

Distributed Energy Storage – the Future of the Industry

The Opinions also promote the deployment of “distributed energy resources in communities, rooftops, and homes through the use of grid-friendly, effective and distributed energy storage.”

Distributed energy storage has attracted a lot of attention for its flexibility, low capital requirements, and value to the consumer by supporting on-site solar generation, demand response, and bill management.

The Opinions also bring up networked management of energy storage devices, calling for energy storage device databases, remote operation and control of distributed storage devices, and energy storage cloud platforms. It encourages modular system design, standardization, networked control over second-life batteries, and support for unhindered and flexible energy exchange. The document also promotes energy storage as a provider of backup power, peak shaving, frequency regulation, and other services.

But because China’s residential electricity rates are so low, residential energy storage is not yet profitable. However, in some industrial parks and among some high-energy consuming businesses, users are beginning to consider solar-plus-storage as a way to reduce electricity bills.

While the present opportunities for energy storage are limited, China remains committed to revolutionizing its energy system. This means that demand response, time-of-use rates and demand charges are likely to grow. As these policies spread and mature, distributed energy storage may well become an attractive market.

The Opinions also mention electric vehicles: “Promote the use of used EV batteries in stationary energy storage. Build an operational EV cloud platform based on elements of the grid, energy storage and distributed energy consumption. Explore the use of electric vehicles in networked platforms to participate in direct energy trading, demand response, and other models.”

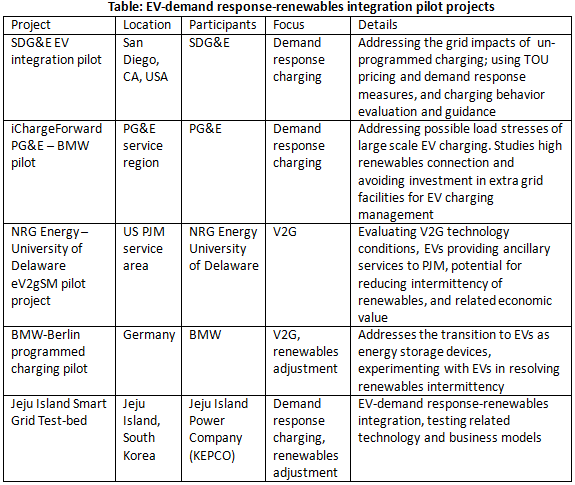

According to official targets, China aims to bring five million electric vehicles to the road by 2020. Electric vehicle charging can have a serious impact on the grid, and so having effective control over distributed EV batteries to provide peak shaving, frequency regulation, or engage in demand response could help maximize the value of electric vehicles.

According to the Opinions, the rollout of the Energy Internet model is set to take place in two phases. From 2016 to 2018, the government will support pilot demonstration projects of different types and scales. From 2019-2025, the emphasis will be on diversification and scaled-up development, and establishing the Energy Internet as a driver of GDP growth.

While its clear that China is a long way from achieving these goals, its telling that national decision-making bodies are endorsing such powerful language to describe their vision of the grid to come. What's most uncertain is how China's vested grid interests will adapt to -- or resist -- these changes.